Wednesday, March 4, 2026

Creationism as Science: Farewell to Newton, Einstein, Darwin...

by Allen Hammond and Lynn Margulis

Published: Sep 18, 2015

Category: Education

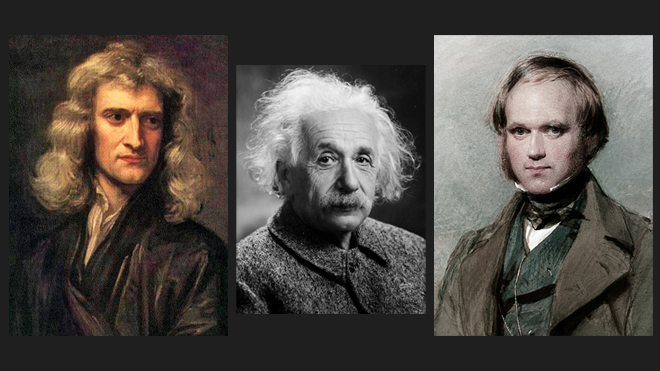

To scientists; the world we live in is remarkable not only for its beauty but also for its consistency, its reasonableness. The same phenomena, obeying the same physical laws, are found in earth bound atoms and in giant, distant galaxies. The same biochemical processes and the same genetic code are found in bacterial cells and in human cells. The great syntheses, the great simplifying ideas of Newton, Darwin, Einstein, and other have in common the discovery of one of these underlying patterns in nature—a pattern that makes sense out of myriad observations, that is logically self-consistent, that holds true whether tested a thousand or a million times. The statement of such a pattern is what we call a scientific theory.

Creationism claims for itself the status of scientific theory, although most observers would describe it as religious belief. For the sake of argument, let us take the creationist assertions seriously as scientific propositions and explore their credibility and their consequences of their adoption. What existing theories, what generally accepted patterns of nature do they challenge? What more consistent explanations do they provide? Such an exercise is possible because both scientists and creationists agree that scientific theories, to be accepted, must agree with the experimental and observational evidence: that is to say, factual rather than mystical reasoning must prevail.

The "theory" for which creationists so fiercely seek equal time in the class-room makes two principal, testable assertions about nature. First, the creationists claim that the age of the Earth and the rest of the known universe is approximately 6,000 to 10,000 years, a figure derived not by measurement but by literal interpretation of the Genesis story in the Bible. And second, the creationists that the present forms of life (plus others now extinct) did not evolve over billions of years but were all created in one week, about 10,000 years ago.

As we shall see, these central tenets of creationism are absolutely inconsistent with the information scientists have gleaned from nature through observation and experiment. Consequently, the creationist claims are also in such direct and dramatic conflict with most modern scientific theories as to be mutually exclusive: Adoption of creationist "theory" requires, at a minimum, the abandonment of essentially all of modern astronomy, much of modern physics, and most of the earth sciences. Much more than evolutionary biology is at stake.

All modern interpretations of astronomical evidence conclude that stars and galaxies are distant objects. Indeed, these distances can be measured for all but the farthest objects, using methods that are not in dispute. Through these methods we know that most stars in our galaxy, and all observable galaxies other than our own, are more than 10,000 light-years away. The light we observe has thus required more than 10,000 years to reach the Earth. Either those objects are more than 10,000 years old, or totally new astronomical hypotheses are needed.

The observed distance scale for astronomical objects can be used to determine the age of the universe. But the distance is just one of three independent lines of astronomical evidence bearing on this question. The other two are the age of the oldest stars (which can be calculated because the color and brightness of stars indicate how long they’ve been burning) and, most accurate of all, the average age of atomic elements is determined by the rate of radioactive decay. All three methods give an age of the universe between 10 and 20 billion years.

The age of the Earth itself is determined primarily by the nuclear physics of radioactivity. The decay rate of a naturally occurring radioactive isotope into a stable atomic form—such as the decay of potassium - 40 into argon - 40 with a half-life of 1.3 billion years—occurs at a constant rate over time, un-effected by external conditions. This constancy, measured in the laboratory but also a direct consequence of quantum theory, allows radioactive isotopes and their decay products to be used as a kind of nuclear clock.

Precise dating is possible with radio-active materials and their decay products found in rocks. Measurements of nuclear clocks based on uranium, potassium, and rubidium in each of thousands of rock samples (from the moon and meteorites as well as from Earth) repeatedly give an age for the solar system of 4.6 billion years. If the Earth is but 10,000 years old, then the nuclear clocks cannot have been constant; radioactive elements must have decayed very much faster in the past than they do today. If so, we need whole new theories of nuclear and subatomic physics. (Since the operation of nuclear reactors also depends on the constancy of radioactive decay, we also face the embarrassment of explaining anew how the devices work.)

Similar contradictions of creationist "theory" can be found in the earth sciences. Modern interpretations of geological, geophysical, and geochemical evidence conclude that the Earth's surface has been drastically rearranged over the course of its history. Huge crustal plates have shifted thousands of miles, whole mountain ranges have been thrust up and then eroded away, trillions of tons of organic materials have been deposited as sediments and then chemically converted to coal beds or petroleum deposits. The rates at which these processes occur, as observed today or as measured in the laboratory, require a history for Earth of hundreds of millions of years. Indeed, for them to have occurred within the past 10,000 years would have required unimaginable conditions and novel physical or chemical processes. If the creationist assertions are to be accepted, then earth scientists must begin, literally from the beginning. (A young age for the Earth also raises question of why, since our species has a written history of nearly 6,000 years, there is no record of dramatic events that would have occurred during that time, such as the opening of the Atlantic Ocean or the collision of India and Asia to form the Himalayas.)

Since science proceeds by the abandonment of one theory only when another can better explain the existing evidence, the creationist "theory" faces severe difficulties. It must not only offer a self-consistent explanation that can account for the accumulated evidence of science—it must offer a more compelling explanation to replace the combined (and self-consistent) edifices of physics, astronomy, and geology. No such theory—no new physical process—has yet been forthcoming. Instead, the creationists attempt to explain away the evidence of an ancient universe by assuming that the evidence itself was created. They posit a world in which the light from distant stars was conveniently created already in transit near Earth. They propose a world in which the radioactive isotope composition of every mineral in the solar system was initially set so as to suggest a much older Earth and which the seabeds and mountaintops were born containing evidence of an early history that never was. In essence, the creationists must propose a deceitful Creator if their hypothesis of a 10,000-year-old world is to deal with the evidence at hand. Most scientists have a more abiding faith in the reasonableness of the world.

What about biological evolution? One line of evidence is closely tied to geology and the nuclear clocks—fossils of bacteria are found in rocks formed more than three billion years ago, animals with skeletons only in rocks formed 600 million years ago, and man like creatures in deposits not older than a few million years. But even if we accept the creationist time scale of 10,000 years for Earth, the biological evidence does not fit the "theory" that all living organisms were independently created in one week.

If chimpanzees were created independently from people, why do they have a common biochemistry down to such exquisite details as the amino acid sequence of particular proteins? For example, cytochrome c, a protein involved in cell metabolic processes, is identical in chimp and man. Even stranger is that the amino acid sequences of the cytochrome c found in bacteria, spinach, horses, and chimps show small changes from one species to another that correlate well with the sequence of appearances of similar organisms in the fossil record. The genetic code itself is the same for all known forms of life. The nucleotides that form the four letters of the code could easily have been different from one species to another, but they are not. A coincidence of special creation, or evidence of common origin?

Evolution is not only inferred; it has also been observed, in the laboratory and in the field. The fantastic variety of dogs—all with common wolflike ancestors—is an evolutionary response to continued human selection pressure. Likewise hundreds of entirely new plant species, from tulips to domesticated corn, have appeared within the span of human history. We value domestic corn, the third most important crop in the world, for its large sweet seeds. But the seeds of Zea mays cannot detach from the cobs to sprout naturally without human intervention. Our ancestors must have guided—forced—its evolution; in an environment without man, this species would be extinct in one year. If evolution is experimental fact, where does that leave the claim of independent creation?

Biologists have no doubt that evolution occurred. They even know what drives it: the growth of any population of organisms beyond the ability of the environment to support them, the appearance of organisms that have novel genetic traits, and the greater growth of some of those variant organisms leading to changed populations over time—the process known as natural selection. But biologists are still debating the details of how it occurs. The theory of evolution, like any other scientific theory, is being continually revised and refined.

For example, one focus of debate at the moment is the rate at which evolutionary change occurs—how gradual or how sudden is the appearance of new species? Another concerns the relative importance of several different mechanisms by which new genetic combinations and new biological traits are formed—how did such novel and complex structures as the eye or the mammalian uterus arise? And how do genetic changes actually translate themselves into a new anatomical form? Scientific meetings on these subjects often generate great disagreements. These disagreements have been misrepresented to the public by creationists as evidence that the theory of evolution is in doubt. On the contrary, they are evidence what is going on is the pursuit of science and not the shoring up of dogma.

All scientific theories, inevitably, are tentative answers to questions about nature. And they incorporate an element of faith that nature is consistent and can be described. But the faith extends only to the intrinsic capacity of people to know, not to the particular theory or object of study. As new facts or new perceptions of nature emerge, scientific theories change too: sometimes subtly, as modern evolutionary theory has changed from Darwin's version; sometimes dramatically, as from Newton’s theory of gravity to that of Einstein. This characteristic of continually revising ideas to reflect the world as it is observed is what makes science science.

In contrast, the creationists start with a "theory" or faith in a particular description of nature drawn not from observation but from the Bible. To argue—as the creationists do —that a theory must be true rather than that the evidence compels one to it as the best choice is fundamentally antithetical to science. To be unwilling to revise a theory to accommodate observation is to forfeit any claim to be scientific. For it is not facts or theories that are essential to the growth of science but rather the process of critical thinking, the rational examination of evidence, and an intellectual honesty enforced by the skeptical scrutiny of scientific peers. By these standards creationism is not science. Indeed, creationists do not participate in the scientific enterprise—they do not present papers or publish in scientific journals. And it is precisely because creationists present themselves as "scientific" that they do most harm to the education system.

As for teaching evolution in the schools—it is ironic that we live in the midst of an epochal revolution in biology, yet schoolchildren cannot learn one of the subject's most fundamental organizing principles except behind closed doors or under clouds of controversy. It is perhaps worth pointing out that the last society to prohibit the teaching of Darwin in the classroom on a large scale was what the fundamentalist preachers often refer to as "godless, atheistic communism"—the Soviet Union under the sway of Lysenko. There, too, the objection was that Darwinian evolution seemed to contradict dogma, and for 30 years it set back Soviet biological science, especially agriculture, at great cost to the Russian people. The parallel should give the creationists cold comfort—stranger bedfellows than the creationists and the commissars cannot be imagined. It should also be adequate cause for alarm among all citizens who see the dangers in attempting to explore matters of science—either in the lab or the classroom—on the basis of doctrine rather than free and critical inquiry.

Lynn Margulis, a micro- and cell biologist, is professor of biology at Boston University.

Allen Hammond, a geophysicist and applied mathematician, is editor of Science 81.

Published in 1981.

Creationism claims for itself the status of scientific theory, although most observers would describe it as religious belief. For the sake of argument, let us take the creationist assertions seriously as scientific propositions and explore their credibility and their consequences of their adoption. What existing theories, what generally accepted patterns of nature do they challenge? What more consistent explanations do they provide? Such an exercise is possible because both scientists and creationists agree that scientific theories, to be accepted, must agree with the experimental and observational evidence: that is to say, factual rather than mystical reasoning must prevail.

The "theory" for which creationists so fiercely seek equal time in the class-room makes two principal, testable assertions about nature. First, the creationists claim that the age of the Earth and the rest of the known universe is approximately 6,000 to 10,000 years, a figure derived not by measurement but by literal interpretation of the Genesis story in the Bible. And second, the creationists that the present forms of life (plus others now extinct) did not evolve over billions of years but were all created in one week, about 10,000 years ago.

As we shall see, these central tenets of creationism are absolutely inconsistent with the information scientists have gleaned from nature through observation and experiment. Consequently, the creationist claims are also in such direct and dramatic conflict with most modern scientific theories as to be mutually exclusive: Adoption of creationist "theory" requires, at a minimum, the abandonment of essentially all of modern astronomy, much of modern physics, and most of the earth sciences. Much more than evolutionary biology is at stake.

All modern interpretations of astronomical evidence conclude that stars and galaxies are distant objects. Indeed, these distances can be measured for all but the farthest objects, using methods that are not in dispute. Through these methods we know that most stars in our galaxy, and all observable galaxies other than our own, are more than 10,000 light-years away. The light we observe has thus required more than 10,000 years to reach the Earth. Either those objects are more than 10,000 years old, or totally new astronomical hypotheses are needed.

The observed distance scale for astronomical objects can be used to determine the age of the universe. But the distance is just one of three independent lines of astronomical evidence bearing on this question. The other two are the age of the oldest stars (which can be calculated because the color and brightness of stars indicate how long they’ve been burning) and, most accurate of all, the average age of atomic elements is determined by the rate of radioactive decay. All three methods give an age of the universe between 10 and 20 billion years.

The age of the Earth itself is determined primarily by the nuclear physics of radioactivity. The decay rate of a naturally occurring radioactive isotope into a stable atomic form—such as the decay of potassium - 40 into argon - 40 with a half-life of 1.3 billion years—occurs at a constant rate over time, un-effected by external conditions. This constancy, measured in the laboratory but also a direct consequence of quantum theory, allows radioactive isotopes and their decay products to be used as a kind of nuclear clock.

Precise dating is possible with radio-active materials and their decay products found in rocks. Measurements of nuclear clocks based on uranium, potassium, and rubidium in each of thousands of rock samples (from the moon and meteorites as well as from Earth) repeatedly give an age for the solar system of 4.6 billion years. If the Earth is but 10,000 years old, then the nuclear clocks cannot have been constant; radioactive elements must have decayed very much faster in the past than they do today. If so, we need whole new theories of nuclear and subatomic physics. (Since the operation of nuclear reactors also depends on the constancy of radioactive decay, we also face the embarrassment of explaining anew how the devices work.)

Similar contradictions of creationist "theory" can be found in the earth sciences. Modern interpretations of geological, geophysical, and geochemical evidence conclude that the Earth's surface has been drastically rearranged over the course of its history. Huge crustal plates have shifted thousands of miles, whole mountain ranges have been thrust up and then eroded away, trillions of tons of organic materials have been deposited as sediments and then chemically converted to coal beds or petroleum deposits. The rates at which these processes occur, as observed today or as measured in the laboratory, require a history for Earth of hundreds of millions of years. Indeed, for them to have occurred within the past 10,000 years would have required unimaginable conditions and novel physical or chemical processes. If the creationist assertions are to be accepted, then earth scientists must begin, literally from the beginning. (A young age for the Earth also raises question of why, since our species has a written history of nearly 6,000 years, there is no record of dramatic events that would have occurred during that time, such as the opening of the Atlantic Ocean or the collision of India and Asia to form the Himalayas.)

Since science proceeds by the abandonment of one theory only when another can better explain the existing evidence, the creationist "theory" faces severe difficulties. It must not only offer a self-consistent explanation that can account for the accumulated evidence of science—it must offer a more compelling explanation to replace the combined (and self-consistent) edifices of physics, astronomy, and geology. No such theory—no new physical process—has yet been forthcoming. Instead, the creationists attempt to explain away the evidence of an ancient universe by assuming that the evidence itself was created. They posit a world in which the light from distant stars was conveniently created already in transit near Earth. They propose a world in which the radioactive isotope composition of every mineral in the solar system was initially set so as to suggest a much older Earth and which the seabeds and mountaintops were born containing evidence of an early history that never was. In essence, the creationists must propose a deceitful Creator if their hypothesis of a 10,000-year-old world is to deal with the evidence at hand. Most scientists have a more abiding faith in the reasonableness of the world.

What about biological evolution? One line of evidence is closely tied to geology and the nuclear clocks—fossils of bacteria are found in rocks formed more than three billion years ago, animals with skeletons only in rocks formed 600 million years ago, and man like creatures in deposits not older than a few million years. But even if we accept the creationist time scale of 10,000 years for Earth, the biological evidence does not fit the "theory" that all living organisms were independently created in one week.

If chimpanzees were created independently from people, why do they have a common biochemistry down to such exquisite details as the amino acid sequence of particular proteins? For example, cytochrome c, a protein involved in cell metabolic processes, is identical in chimp and man. Even stranger is that the amino acid sequences of the cytochrome c found in bacteria, spinach, horses, and chimps show small changes from one species to another that correlate well with the sequence of appearances of similar organisms in the fossil record. The genetic code itself is the same for all known forms of life. The nucleotides that form the four letters of the code could easily have been different from one species to another, but they are not. A coincidence of special creation, or evidence of common origin?

Evolution is not only inferred; it has also been observed, in the laboratory and in the field. The fantastic variety of dogs—all with common wolflike ancestors—is an evolutionary response to continued human selection pressure. Likewise hundreds of entirely new plant species, from tulips to domesticated corn, have appeared within the span of human history. We value domestic corn, the third most important crop in the world, for its large sweet seeds. But the seeds of Zea mays cannot detach from the cobs to sprout naturally without human intervention. Our ancestors must have guided—forced—its evolution; in an environment without man, this species would be extinct in one year. If evolution is experimental fact, where does that leave the claim of independent creation?

Biologists have no doubt that evolution occurred. They even know what drives it: the growth of any population of organisms beyond the ability of the environment to support them, the appearance of organisms that have novel genetic traits, and the greater growth of some of those variant organisms leading to changed populations over time—the process known as natural selection. But biologists are still debating the details of how it occurs. The theory of evolution, like any other scientific theory, is being continually revised and refined.

For example, one focus of debate at the moment is the rate at which evolutionary change occurs—how gradual or how sudden is the appearance of new species? Another concerns the relative importance of several different mechanisms by which new genetic combinations and new biological traits are formed—how did such novel and complex structures as the eye or the mammalian uterus arise? And how do genetic changes actually translate themselves into a new anatomical form? Scientific meetings on these subjects often generate great disagreements. These disagreements have been misrepresented to the public by creationists as evidence that the theory of evolution is in doubt. On the contrary, they are evidence what is going on is the pursuit of science and not the shoring up of dogma.

All scientific theories, inevitably, are tentative answers to questions about nature. And they incorporate an element of faith that nature is consistent and can be described. But the faith extends only to the intrinsic capacity of people to know, not to the particular theory or object of study. As new facts or new perceptions of nature emerge, scientific theories change too: sometimes subtly, as modern evolutionary theory has changed from Darwin's version; sometimes dramatically, as from Newton’s theory of gravity to that of Einstein. This characteristic of continually revising ideas to reflect the world as it is observed is what makes science science.

In contrast, the creationists start with a "theory" or faith in a particular description of nature drawn not from observation but from the Bible. To argue—as the creationists do —that a theory must be true rather than that the evidence compels one to it as the best choice is fundamentally antithetical to science. To be unwilling to revise a theory to accommodate observation is to forfeit any claim to be scientific. For it is not facts or theories that are essential to the growth of science but rather the process of critical thinking, the rational examination of evidence, and an intellectual honesty enforced by the skeptical scrutiny of scientific peers. By these standards creationism is not science. Indeed, creationists do not participate in the scientific enterprise—they do not present papers or publish in scientific journals. And it is precisely because creationists present themselves as "scientific" that they do most harm to the education system.

As for teaching evolution in the schools—it is ironic that we live in the midst of an epochal revolution in biology, yet schoolchildren cannot learn one of the subject's most fundamental organizing principles except behind closed doors or under clouds of controversy. It is perhaps worth pointing out that the last society to prohibit the teaching of Darwin in the classroom on a large scale was what the fundamentalist preachers often refer to as "godless, atheistic communism"—the Soviet Union under the sway of Lysenko. There, too, the objection was that Darwinian evolution seemed to contradict dogma, and for 30 years it set back Soviet biological science, especially agriculture, at great cost to the Russian people. The parallel should give the creationists cold comfort—stranger bedfellows than the creationists and the commissars cannot be imagined. It should also be adequate cause for alarm among all citizens who see the dangers in attempting to explore matters of science—either in the lab or the classroom—on the basis of doctrine rather than free and critical inquiry.

Lynn Margulis, a micro- and cell biologist, is professor of biology at Boston University.

Allen Hammond, a geophysicist and applied mathematician, is editor of Science 81.

Published in 1981.